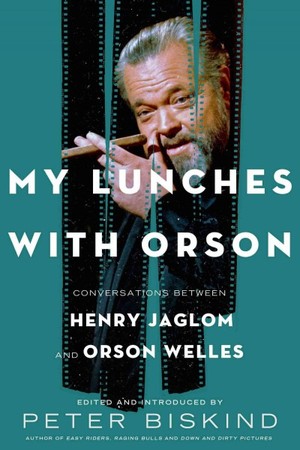

Have you ever wished you could be a fly on the wall of a brilliant conversationalist, a raconteur, an artist who freely speaks out on just about everyone and everything in his world? That’s just what readers of the new book, My Lunches with Orson: Conversation Between Henry Jaglom and Orson Welles, get to do. Yes, it’s the OrsonWelles, the man who made what many consider the greatest film ever made. Welles, of course, was also a respected actor, though he sold his services in many bad films for the money to make his own. Welles also indulged in pushing second rate products in ads like Paul Masson wine and would pop up on talk shows every other week. He was a man of taste and contradiction.

Have you ever wished you could be a fly on the wall of a brilliant conversationalist, a raconteur, an artist who freely speaks out on just about everyone and everything in his world? That’s just what readers of the new book, My Lunches with Orson: Conversation Between Henry Jaglom and Orson Welles, get to do. Yes, it’s the OrsonWelles, the man who made what many consider the greatest film ever made. Welles, of course, was also a respected actor, though he sold his services in many bad films for the money to make his own. Welles also indulged in pushing second rate products in ads like Paul Masson wine and would pop up on talk shows every other week. He was a man of taste and contradiction.

The book compiles a series of conversations recorded during the last years of Welles fascinating life. The original tapes remained “lost” for years until editor, Peter Biskind (Easy Riders, Raging Bulls; Down and Dirty Pictures), urged independent filmmaker Henry Jaglom to have them transcribed. What’s revealed is a fascinating, paradox study of a cinematic genius who knew even in his final years that he was better and brighter than just about anyone else in town.

By this time in his life Welles was arthritic and mostly confined to a wheelchair, yet his mind and wit were as sharp as ever. Jaglom and Welles probably made for an “odd couple.” The young director was part of the New Hollywood of Dennis Hopper, Peter Fonda and Bert Schneider; a quirky filmmaker (Tracks, A Safe Place, Eating), while Welles for all his independence was old school. What they had in common was “a fierce desire to go their own way” as Peter Biskind states in his introduction to the book. Jaglom first met Welles when he nervously was trying to figure out how to convince the great man to play a part in his first feature film. It was a few years later while making his second film, “Tracks,” that Jaglom ran into Welles at Ma Maison, Welles favorite restaurant, and Welles agreed to their conversations being recorded as long as the recorder remained out of sight.

By this time in his life Welles was arthritic and mostly confined to a wheelchair, yet his mind and wit were as sharp as ever. Jaglom and Welles probably made for an “odd couple.” The young director was part of the New Hollywood of Dennis Hopper, Peter Fonda and Bert Schneider; a quirky filmmaker (Tracks, A Safe Place, Eating), while Welles for all his independence was old school. What they had in common was “a fierce desire to go their own way” as Peter Biskind states in his introduction to the book. Jaglom first met Welles when he nervously was trying to figure out how to convince the great man to play a part in his first feature film. It was a few years later while making his second film, “Tracks,” that Jaglom ran into Welles at Ma Maison, Welles favorite restaurant, and Welles agreed to their conversations being recorded as long as the recorder remained out of sight.

The book reveals Welles to be a paradoxical mix of genius, cantankerousness, pettiness, and always darkly humorous. When Richard Burton, uninvited, approaches their table one day to say hello, Welles brushes him off like he was an annoying fly. He explained to Jaglom that Burton, by marrying Elizabeth Taylor, threw his career away. Yet on another occasion, he warmly welcomes Jack Lemmon to the table. Welles rips into John Huston, “His first picture,” Welles says, The Maltese Falcon, was totally borrowed from Kane. Jaglom agrees, pointing to the similarities in the lighting, the camera angles and the setups. He disliked John Ford’s, The Searchers, thought Joan Fontaine’s performance in Jane Eyre was bad and that she and her sister Olivia de Havilland could not act. Then there’s Woody Allen whose movies he hated; Irving Thalberg “was Satan,” he didn’t like Spencer Tracy yet he could not understand why Kate Hepburn did not like him. He could not comprehend the love for studio directors like Howard Hawks, Ford and even Hitchcock. Though Welles was a well-known liberal he enjoyed talking more to right-wingers like John Wayne and Ward Bond because they were nicer than liberals. As for Charlie Chaplin, he thought The Little Tramp was a genius, yet he also states there is nothing Chaplin ever made that was as good as Buster Keaton’s, The General, a film he considered one of the greatest works ever made. He loved Chaplin’s City Lights but thought Modern Times was “coarse.” The tales are all intriguing and are not limited to films and filmmakers. Welles during his lifetime met many well known people in all fields, Churchill, Roosevelt among them and he freely expresses he thoughts about these historical figures, both good and bad.

But don’t think Welles was all negative, he was not. He loved Lon Chaney, “One of the great movie actors” and admired Charles Laughton, especially his performance in Rembrandt. Like many of us, he is influenced the most by those artists from his youth. He also talks how seeing films now, for him is not a pure experience, unable to “erase those years of experience.” Welles explains, “I don’t see movies as purely as I ought to see them. Before I started making movies, I’d get into them, lose myself. I can’t do that now. That’s why I don’t think my opinions about movies are as good as somebody’s who doesn’t have to look at them through all those filters.”

But don’t think Welles was all negative, he was not. He loved Lon Chaney, “One of the great movie actors” and admired Charles Laughton, especially his performance in Rembrandt. Like many of us, he is influenced the most by those artists from his youth. He also talks how seeing films now, for him is not a pure experience, unable to “erase those years of experience.” Welles explains, “I don’t see movies as purely as I ought to see them. Before I started making movies, I’d get into them, lose myself. I can’t do that now. That’s why I don’t think my opinions about movies are as good as somebody’s who doesn’t have to look at them through all those filters.”

Welles and Jaglom also talk a lot about his own career, how he became the boy genius of Hollywood until Kane came out and flopped financially. While he made other films it was always a struggle and he never really recovered as a director. He made ends meet by acting in good films like “The Third Man” and sometimes in junk. He additionally appeared in commercials where he could use his commanding voice to its advantage. For years, Welles was also a regular guest on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show where he did everything from magic to reading Shakespeare. He thought The Third Man was Carol Reed’s greatest film with Odd Man Out a very close second though both he and Jaglom considered James Mason’s performance poor. He hated reading about himself because he believed all the bad stuff that was written about whether it was true or not.

Welles was the most acclaimed director of his generation yet he could not get a film financed. Throughout the book we hear discussions about potential financing of new films, one in particular was a script called My Brass Ring, but each potential source would fail for one reason or another including Welles own self destruction.

Welles was the most acclaimed director of his generation yet he could not get a film financed. Throughout the book we hear discussions about potential financing of new films, one in particular was a script called My Brass Ring, but each potential source would fail for one reason or another including Welles own self destruction.

As the book jacket states, Welles was ” a man struggling with reversals, bitter and angry, desperate and for one last triumph, but crackling with wit and a restless intelligence.” While the conversations are more gossipy than Peter Bogdanovich’s earlier, more academic book of conversations, This is Orson Welles, My Lunches with Orson: Conversations Between Henry Jaglom and Orson Welles is a can’t put down read. Each chapter is more fascinating that the last. You absolutely feel as if you were sitting at a nearby table and listening in on the private, the intelligent, the witty and juicy conversations of a genius. All part of the books’ charm, even if you feel sometimes a little uncomfortable afterward for listening in.

A review copy of My Lunches with Orson: Conversation Between Henry Jaglom and Orson Welles was provided by Metropolitan Books (Henry Holt and Company).

I’ve read a few reviews of this now and it sounds really entertaining. Although, I do take exception with Welles saying Olivia de Havilland couldn’t act.

LikeLike

Kim, Welles does knock a lot of films and people who many, including myself, think are good but he admits himself in the book that he may not be the best judge. He’s too jaded and probably was somewhat bitter about his career too.

LikeLike

Whoa! Don’t hold back, Orson. Tell us what you really think.

Just kidding! This sounds like a fascinating read. Excellent review.

LikeLike

Orson’s not shy about what he says. That’s one of the fascinating aspects of this book. Thanks SS!

LikeLike

Sounds fascinating and like the sort of book which would get you arguing back as you read! Great review, John.

LikeLike

It’s really quite fascinating to read. Thanks Judy!

LikeLike

John, I’m not surprised that Orson Welles was both a complicated actor and filmmaker, and a complicated person in general! Then again, it wouldn’t be such a fascinating read otherwise! 🙂 Great review, my friend!

LikeLike

Sorry for the delay Dorian. Somehow this slipped by. If you get the chance, you should read this, it’s fascinating.

LikeLike

Fine review, John, and I agree with your assessment of the book. My only real quibble is that it lacks an index. That would have been helpful.

LikeLike

Thanks Rick. I agree with you on an index being helpful.

LikeLike

Does Welles really give a blanket derogation of Ford’s work in his conversations with Jaglom? He had, after all, so famously adopted a hagiographic approach to Ford in his 1967 “Playboy” magazine interview with Kenneth Tynan, where – after he expressed his admiration for contemporary American directors Stanley Kubrick and Richard Lester – he expressed his admiration for “the old masters. By which I mean John Ford, John Ford, and John Ford.[…] With Ford at his best, you feel that the movie has lived and breathed in a real world.” I guess I should read the Jaglom conversations for myself.

LikeLike

Jan, There could be a few reasons for the contradictions 1) The Jaglom conversations were never meant for publication though Welles knew he was being recorded. In a relaxed atmosphere between two friends things are sometimes said that are different from the more public statements. 2) The interviews were about 20 years apart. Welles career as a director was over. He may have built up years of bitterness toward others who were more successful in Hollywood, or at least knew how to play the game better than he could, and it came out in these conversations. 3) Many people are not always consistence in what they say or with ideas they express. Over time, new information, new experiences, feelings and ideas change. These are only my thoughts for what they are worth.

The book, however you take it, is definitely a fascinating read.

LikeLike