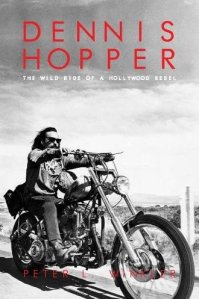

Peter L. Winkler’s new biography, “Dennis Hopper: The Wild Ride of a Hollywood Rebel” is just that, a wild, informative, thrilling, readable ride of an iconic life that was constantly evolving. The book is as colorful as its subject. Peter is a film historian who has written for a variety of publications, including Cinefan, Filmfax, Crimemagazine.com, Playboy, and Video Theater. This is Part One of our phone conversation that took place on October 12th.

John: Is this your first book?

Peter: Yes, it is.

John: Would you tell us a little about your professional background?

Peter: I attended the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) from 1974–1978. I graduated in 1978, receiving a Bachelor of Arts in History with academic honors. Then I entered law school, the last refuge for liberal arts majors who don’t know what to do next. The rheumatoid arthritis that afflicted when I was nine years old became much worse, and I was stricken with secondary Sjogren’s Syndrome, which became disabling. I didn’t practice law. I didn’t do much of anything, so I figured, well, you know, I was always a good academic writer, so I thought maybe I had what it took to be a professional writer. I purchased my first computer in 1985, a laptop; I’ve owned nothing but laptops, because it’s hard for me to sit at desks for long periods. I sold the first article I wrote, which was good beginners luck.

John: Really.

John: So you did all your own research?

Paul: I did my own research. I did everything except crank the printing press and bind the pages. I wrote my own dusk jacket copy, procured the blurbs, I did it all, and here it is!

John: What made you decide on or should I say select Dennis Hopper as a subject?

Peter: You interviewed Patrick McGilligan, who blurbed my book. In 1997 he gave an interview to a website called Beatrice, which has a lot of very good author interviews archived there, and they asked him the same question. What draws you to a certain subject and he said, “The honest answer is always the contract. There’s a dishonest answer: ‘The subject is personally fascinating and has a deep personal subtext for me . . .’ ” After striking out with a book proposal for a biography of actor Nick Adams, I decided next time out, I am going to find a biographical subject where lack of name recognition is certainly not a problem. Dennis Hopper is an iconic or near iconic figure in film and there should be no problem there. He led a very rich and eventful life which was quite colorful. He was quite the character himself. So I figure it was something I could probably sell, it’s marketable, and it turned out that it was, of course.

John: One of the things I found ironic was that Hopper was born in Dodge City, Kansas, a city with the history of being part of the Wild West, and it seemed his life was that of an outlaw, he had that outlaw mystique.

Peter: Dennis Hopper was an authentic rebel. He rebelled against his parents first. He rebelled against authority; he rebelled against film directors, so he certainly was an authentic rebel.

John: He had a troubled life with his parents but the other thing I noticed is that right from his youth he knew he wanted to be an artist.

John: He had a troubled life with his parents but the other thing I noticed is that right from his youth he knew he wanted to be an artist.

Peter: Hopper said that he knew he wanted to be an actor the first time he saw a movie. He said his childhood was very unhappy, he was very lonely, and he had a troubled relationship with his parents, and he came up with the idea, at some point in his young life, that if he became an artist and created works of art important enough to astonish people and make them say, “Wow!” he would be able to win their love and affection.

John: So a lot of his desire stem from a search for approval.

Peter: Exactly. Hopper said the creative drive “comes out of a lonely, sad place. It’s a way of looking for acceptance, which is almost impossible to find. Acting comes out of that place, too.”

John: Once his career started, he got off to a quick start; he did not go through years of practicing his craft. He got a couple of TV shows quickly and then he got a contract with Warner Brothers and soon got a role in “Rebel Without a Cause” which started his fascination and idolatry of James Dean.

Peter: Yes, it did.

John: …and that, Dean, seemed to haunt him throughout his career.

Peter: Yes, absolutely. Hopper was, if you want to call it, the proverbial overnight discovery as you said. He had only acted in a couple of TV shows when he played a teenage epileptic in an episode of the TV series “Medic” and his performance, especially his epileptic seizures, impressed a lot of viewers. Three movie studios called his agent to request interviews with Hopper and he ended up at Warner Bros., where his first role was an uncredited bit part in “I Died a Thousand Times.” His second film was “Rebel Without a Cause,” where he had a small but noticeable role as Goon, a member of the gang that harasses James Dean’s character. Hopper’s fascination with Dean began with “Rebel,” as soon as he saw Dean act. Knowing that he was going to be acting with Dean, Hopper had gone to see “East of Eden,” which was Dean’s only film released while he was still alive. When Hopper first saw Dean in person, Dean was walking down a hallway at Warner Bros., unshaven, disheveled, wearing glasses, with a cigarette dangling from his lower lip. Hopper did a double take when his agent whispered, “That’s James Dean.” Hopper couldn’t believe it was the same person he just watched on screen. When Hopper watched Dean work on the set of “Rebel,” he was blown away by his spontaneity, and the fact that Dean did not stick to what was written in the script and freely improvised, pulling “miracles out of the air” as Hopper put it. Hopper wanted to know how you do that. Hopper’s previous training had only been in classical theater, where every line reading and gesture was on the page and preconceived in advance.

John: I got the impression Dean was both a good and bad influence on Hopper. It seemed he felt he had to, or wanted to, carry on Dean’s legacy once he died.

John: I got the impression Dean was both a good and bad influence on Hopper. It seemed he felt he had to, or wanted to, carry on Dean’s legacy once he died.

Peter: He did, he did. Hopper said, “He [Dean] was also a guerilla artist who attacked all restrictions on his sensibility. Once he pulled a switchblade and threatened to murder his director. I imitated his style in art and in life. It got me into a lot of trouble.”

John: His second film was “Giant.” He worked with George Stevens on that one and Stevens way of working was totally different from the way Nick Ray worked. Ray was much more into the improvisation that Dean did where I believe Stevens was more of here’s what you do…

Peter: Stevens viewed actors as complete entities with fixed characteristics. He cast them for what he saw as their acting resources, based on their performances in other films. Stevens believed that you put actors on the set, you get the scene ready to go, you yell “Action,” and they do their thing. He didn’t really work with actors the way Ray did. Ray was much more receptive to letting Dean and other actors suggest things, and improvise; there was a lot more freedom there.

John: Hopper had some small parts in other films and TV shows, but then came a film he made with director Henry Hathaway which led to his exile. What exactly happened?

John: Hopper had some small parts in other films and TV shows, but then came a film he made with director Henry Hathaway which led to his exile. What exactly happened?

Peter: Warner Bros. loaned Hopper out to 20th Century-Fox for a Western called “From Hell to Texas.” It was made in ’57 or ’58; it was released in ’58. Dennis Hopper played the weak son of a bad man, who was played by R. G. Armstrong, a character actor you see in a lot of Westerns. Henry Hathaway was a veteran director who had come up from being a prop man and worked his way up and was a very tough guy, an old-fashioned autocrat. Don Murray, who played the lead in the film, said, “Hathaway had a reputation. I had heard about Hathaway, going into this film, of being a very, very volatile director and getting very angry and having all sorts of emotional outbreaks himself on the set, sort of like Otto Preminger, very dictatorial in his ways.” Hopper formed the mistaken conclusion that James Dean really directed “Rebel Without a Cause,” because Nick Ray was perceptive enough to entertain Dean’s ideas and let him incorporate them in his performance. Hopper wanted to be in charge of his performance, the way Dean had. Hopper said that Hathaway wanted him to imitate Marlon Brando in his timing and gestures and wanted him to give certain line readings, make certain physical gestures. Hopper refused Hathaway’s direction, and he decided that this was going to be his break for artistic freedom, his chance to exercise the creative prerogative that Brando, Clift, and Dean enjoyed. He was going to do what he wanted to do, and of course it resulted in Hathaway constantly yelling and screaming at him. Hathaway shot many takes of scenes because he was frustrated that Hopper wasn’t following his directions. Don Murray recalled Hathaway shooting 22 takes of a scene when Hopper said, “Go fuck yourself” and walked right off the set. Hopper walked off the film three times and each time, Hathaway invited him to dinner, where Hathaway couldn’t be more charming. They would have wonderful dinners. When Hopper discussed his ideas for the following day’s scenes, Hathaway said, “Sure, sure kid. Whatever you say.” On the set the next day, Hathaway was a monster again, yelling and screaming at Hopper. “Mr. Hathaway, last night at dinner, you said I could try this,” Hopper reminded him. Hathaway told him, “Forget that, it’s fuckin’ dinner talk, kid. We’re makin’ a movie here, now get the fuck over there, and hit your mark, and say your lines like I tell ya!”

John: (laughing)

Peter: The tension between Hathaway and Hopper culminated on the last day of filming, when Hopper had a ten-line scene with the actor playing his father in the film. He arrived on the set and Hathaway had all these cans of unexposed film stacked around, and he pointed to them and said, “You see those kid, you know what those are?” “Yeah,” Hopper says, “they’re film cans.” Hathaway said, “Yeah those are film cans. There’s enough film in there to shoot for four months. And you’re going to do the scene my way. You’re going to pick up the coffee cup and put it down. You’re gonna read the lines this way. And you can do it that way, or you can make a career out of this one scene in this one movie because I own 40 percent of this studio. We’re here now to stay. We’ll send out for lunch, send out for dinner, we’re here. Sleeping bags will be brought in. This is it.”

They started at seven in the morning. By eleven o’clock, Hopper was getting calls from executives from Warner Bros., saying, “What the hell are you doing over there? Just do the scene the way Hathaway wants and get back here.” Hopper claimed that even Jack Warner called him. It just went on because Hopper didn’t want to surrender to Hathaway in this titanic battle of wills. Hathaway was determined to break Hopper. By ten o’clock, Hopper buckled. “I couldn’t figure out another way to do the scene,” he said. “By this time all the executives from Fox—Warner, everybody—were all there. It was big news. ‘You want to see Hathaway and Hopper freaking out? Come on over.’ I said, ‘Just tell me what you want.’ And I broke down and started crying. I said, ‘Just tell me one more time what you want.’ I did the scene.” Hathaway came over to Hopper, and without removing his cigar from his mouth, said, “Kid, there’s one thing I can promise you: you’ll never work in this town again.” Ironically, it was Hathaway who hired Hopper again for a major movie, “The Sons of Katie Elder,” in 1965. Until then, Hopper worked in episodic TV and some low-budget films. He didn’t work in major films at all. Though “Key Witness” was made at MGM, it was still a low-budget film. Warner Bros. dropped him from his contract because of the Hathaway incident, also because they wanted to put him into a TV series and he didn’t want to do a TV series. Hopper wanted to go to New York and study at the Actors Studio under Lee Strasberg. He studied there and commuted between New York and Hollywood for guest shots on episodic TV shows. In 1965 Hathaway and John Wayne decided to take pity on him. Hopper had married Brooke Hayward in 1961, they had their first child, and as Hathaway put it, she’s a nice Irish kid, and her mother Margaret Sullavan, was a nice Irish woman, “So Duke and I decided it’s time for you to go back to work.”

They started at seven in the morning. By eleven o’clock, Hopper was getting calls from executives from Warner Bros., saying, “What the hell are you doing over there? Just do the scene the way Hathaway wants and get back here.” Hopper claimed that even Jack Warner called him. It just went on because Hopper didn’t want to surrender to Hathaway in this titanic battle of wills. Hathaway was determined to break Hopper. By ten o’clock, Hopper buckled. “I couldn’t figure out another way to do the scene,” he said. “By this time all the executives from Fox—Warner, everybody—were all there. It was big news. ‘You want to see Hathaway and Hopper freaking out? Come on over.’ I said, ‘Just tell me what you want.’ And I broke down and started crying. I said, ‘Just tell me one more time what you want.’ I did the scene.” Hathaway came over to Hopper, and without removing his cigar from his mouth, said, “Kid, there’s one thing I can promise you: you’ll never work in this town again.” Ironically, it was Hathaway who hired Hopper again for a major movie, “The Sons of Katie Elder,” in 1965. Until then, Hopper worked in episodic TV and some low-budget films. He didn’t work in major films at all. Though “Key Witness” was made at MGM, it was still a low-budget film. Warner Bros. dropped him from his contract because of the Hathaway incident, also because they wanted to put him into a TV series and he didn’t want to do a TV series. Hopper wanted to go to New York and study at the Actors Studio under Lee Strasberg. He studied there and commuted between New York and Hollywood for guest shots on episodic TV shows. In 1965 Hathaway and John Wayne decided to take pity on him. Hopper had married Brooke Hayward in 1961, they had their first child, and as Hathaway put it, she’s a nice Irish kid, and her mother Margaret Sullavan, was a nice Irish woman, “So Duke and I decided it’s time for you to go back to work.”

John: That’s a fascinating story. During this period of exile didn’t Hopper get interested in painting and photography at that time? Wasn’t it James Dean who actually got him to pick up a camera?

Peter: He was already painting as a child. He took art classes at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri. When Hopper moved to Hollywood he looked up Vincent Price, who he met at the La Jolla Playhouse when he was an apprentice there, and Price showed him his abstract expressionist art, which Hopper fell in love with, and that became one of Hopper’s two favorite modes of artistic expression. The other, later on, was Pop Art. James Dean was kind of a photographic dilettante. A lot of Hopper’s interests could probably be viewed as imitations of what Dean was doing, or maybe Hopper himself was interested in it, but when he saw Dean do it, he emulated him. He was modeling himself after Dean. When Dean saw that Hopper was also interested in photography, he gave him some advice, telling him never crop your photographs, always shoot full frame the way you shoot a film frame, because you can’t crop an image in the movie camera. Hopper later said he used photography to prepare himself to direct films, because he hoped to direct, so he took that advice from Dean, and never cropped his photographs.

John: But he did get some professional assignments. Didn’t he sell some stuff for Harpers Bazaar?

Winkler: By the mid-sixties, word of Hopper’s photographic skill reached New York and he got assignments from Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, where he did some celebrity photo shoots of people like Paul Newman. He also photographed people who were to become stars later, like his friends Peter and Jane Fonda, and he photographed the avant-garde artists that he knew, so his photographs now have a kind of documentary quality of the period.

John: You mentioned his interested in Pop Art. Didn’t he buy a Warhol Campbell’s Soup Can painting for seventy-five dollars?

Peter: Yes, for seventy-five dollars. On June 26, 1962, the day his and Brooke Hayward’s daughter was born, he bought it at the Dwan gallery. When he got to the hospital and his daughter was presented to him, he told his wife he had just bought this painting for seventy-five dollars and he was very excited about it. Brooke Hayward said, “He was on the cutting edge. Dennis had an eye and an ear for what was happening at that time. He was on the scene. If you wanted to know something about what the scene was, Dennis could tell you.”

John: When did he meet Peter Fonda?

Peter: Hopper met Peter Fonda on August 9, 1961, after Hopper’s wedding to Brooke Hayward. Her parents, who opposed her wedding to Hopper, stayed just long enough to see her take her vows and left the church. When Brooke and Dennis walked out on the steps of the church, there was nobody there, there was no reception. So Jane Fonda, who was a lifelong friend of Brooke Hayward, held a little reception at her apartment in New York and that’s when Peter Fonda met Dennis Hopper. Fonda said, “And I thought, ‘This guy is looney tunes, but he sure is interesting.’ ”

John: Just before we go on to “Easy Rider,” Hopper was in a Roger Corman film called “The Trip” and I believe he did some second unit work on that. Was that the first time he did any kind of directing?

Peter: Yes. On “The Trip,” Hopper and Peter Fonda decided to put together a little second unit, where they got a cameraman and went out to shoot some scenes that were in the screenplay which cheapskate Roger Corman decided not to film. Hopper directed some footage of Fonda in the California desert, which Fonda thought was beautiful. Hopper’s second unit direction isn’t acknowledged in the film’s credits. Hopper’s work convinced Fonda that he had the potential to direct “Easy Rider.”

John: One of the most fascination parts of the book is the whole part dedicated to “Easy Rider.” It seems that the genesis of the film seems to remain questionable. Whoever is talked too seems to take credit, even whose idea it was?

John: One of the most fascination parts of the book is the whole part dedicated to “Easy Rider.” It seems that the genesis of the film seems to remain questionable. Whoever is talked too seems to take credit, even whose idea it was?

Peter: After “Easy Rider” became successful, a couple of people claimed they had a hand in coming up with the story for the film. John Gilmore was a friend of James Dean. Through Dean, he met Hopper when he shadowed Dean during the making of “Rebel Without a Cause.” Gilmore said he wrote an outline for a film for a producer named Michael Macready, who was the son of George Macready, the actor. Gilmore claims that his story followed the exploits of two guys on bikes who score big on a cocaine deal and end up getting blown away by a stranger with a shotgun. When the rights reverted to him, Gilmore said he showed his story to Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda, who were very enthusiastic about it. Gilmore claimed they promised him that if American International Pictures (AIP) green-lighted the film, he would get a story credit and payment even if his script wasn’t used. When the deal with AIP fell through, Gilmore says that Hopper said that he and Peter Fonda were developing Fonda’s idea, called “Riding Easy,” whose storyline sounded almost identical to Gilmore’s, and they had hired Terry Southern to develop a treatment. Deprived of any credit or compensation for his story, Gilmore still feels that Hopper cheated him of his rightful due.

Then there was a Hell’s Angel named Sweet William, who was a member of a little counterculture group from the Haight-Ashbury district in San Francisco called the Diggers that included actor Peter Coyote. Coyote said that they were chewing the fat one time with Hopper in LA when Sweet William said, “You know what I’d do? I’d make a movie about me and a buddy just riding around. Just going around the country doing what we do, seeing what we see, you know. Showing the people what things are like.” But I think it’s pretty well established Peter Fonda came up with what you could call the germ or kernel of the idea for the movie. He was at a movie exhibitor’s convention in Toronto promoting “The Trip,” which he starred in, in late September 1967. One evening in his hotel room, high on beer and pot, he was looking at a publicity photo for “The Wild Angels” with Bruce Dern and himself on a motorcycle and a light bulb went on over his head. He thought, what if instead of two guys on a chopper, we had each one on their own chopper. In 1970, Fonda told Playboy’s interviewer, “And suddenly I thought, that’s it, that’s the modern Western. Two cats just riding across the country, two loners, not a motorcycle gang, no Hell’s Angels, nothing like that, just those two guys. And maybe they make a big score see, so they have a lot of money. And they’re going to cross the country and retire in Florida.” He also claimed he conceived the film’s shock ending that night, where the bikers get blown away by two rednecks in a pickup. Fonda proposed it to AIP and they were interested because he had one more picture to make on a three-picture contract. Fonda called up Dennis Hopper from his hotel room, described his story to Hopper and said, “We’ll both co-star, we’ll both write it together and you’ll direct it.” Hopper of course, who at that point could barely get arrested in Hollywood, was all for it, because his big dream was to direct a film.

John: How did Terry Southern get involved?

John: How did Terry Southern get involved?

Peter: Peter Fonda was in the French coastal town of Roscoff, where he acting in the film “Spirits of the Dead,” a trilogy of stories loosely based on Edgar Allan Poe that was made because the Roger Corman Poe films had been so successful. His segment of the film, which also featured Jane Fonda, was being directed by Roger Vadim, her husband at the time, who had just directed her in “Barbarella.” Terry Southern, one of the credited screenwriters on “Barbarella,” had been in Rome supervising some of the editing. He flew down to Roscoff, and when he met Peter Fonda, he starting chatting with him and asked him what he was up to. Fonda mentioned the project that he and Dennis Hopper were trying to develop, which became “Easy Rider,” and said they were looking for a writer. According to Fonda, Southern was very excited by the story’s possibilities, and said, “I’m your man.” Peter Fonda said, “Terry, your salary is more than the budget of our whole movie!” At that point, Southern had co-written “Dr. Strangelove,” he’d adapted Evelyn Waugh’s novel, “The Loved One,” and he wrote “The Cincinnati Kid.” Terry Southern was then at the peak of his career in Hollywood. Southern replied, “No, no, no. You don’t get it! It’s the most commercial story I have ever heard. And a real pip of an ending! I’m your man!” Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper held story conferences with Terry Southern at his apartment in New York, where they brainstormed ideas while Southern wrote things down on his legal pad and culled the best ideas, and then wrote the screenplay, although there is a controversy over that, due to Dennis Hopper’s later claims that he alone wrote it and nobody else had anything else to do with the writing.

John: It seemed that Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda had a rocky relationship. They were friends but they always seemed to be at each other’s throat a lot of times.

Peter: I think it was largely Dennis Hopper’s fault. Hopper had a fractious personality, and he was paranoid, as he even admitted. Anything he thought he had originated or conceived was touched with genius, and he became almost obsessively protective of it, so if anybody else challenged him about it, he would become very volatile, he could become explosive verbally and sometimes even physically. Yeah, they did argue, they did have fights. It happened in New Orleans, where they filmed the portion of “Easy Rider” where Fonda and Hopper’s characters go to a cemetery with two whores and drop acid. Hopper wanted Fonda to climb up on what he called this Italian statue of liberty which was over a tomb and have his character talk to it like it was his mother, and ask, “Why did you cop out on me?, Why did you abandon me?”, because Hopper had gained Peter Fonda’s confidence as a friend and learned what the public never knew, which was that Fonda’s mother cut her throat from ear to ear in an insane asylum when Peter was a child. Peter Fonda did not want to do the scene, and they argued and argued, until finally Peter said, “Give me one good reason to do it,” and Hopper, who was at that point tearful, said, “Because I’m the director, man!” Peter Fonda found that logic hard to refute, so he climbed into the statue’s arms and did the scene, but that was really the break in their friendship. And William Hayward, Brooke Hayward’s brother, the film’s associate producer, said they fought throughout the remainder of the picture even though they appeared to be good friends for public consumption. Dennis Hopper later said all sorts of things, Peter Fonda was never my friend, Peter Fonda tried to take away the one thing I created, which was “Easy Rider,” because Fonda wanted to back out of the film after the New Orleans scenes were shot. He didn’t want to have anything more to do with the film, he though Hopper was out of control, the whole thing was going to be a disaster. Their friendship terminated at that point.

John: “Easy Rider” changed Hollywood, and Hopper’s ego which seemed pretty big to start, seemed grow even more.

Peter: Dennis Hopper thought he was a genius and he was determined to get others to recognize his genius, and to him the success of “Easy Rider” validated everything he did, whether it was his creative choices or his personal behavior, which was excessive and ultimately self-destructive.

End of Part One

Click here for a link to Part Two of my interview with Peter L. Winkler.

Absolutely fascinating. Great interview, John. & looking forward to Pt. II…

LikeLike

Thanks Eve, appreciate it. i am going to be sending you an e-mail shortly on another topic we discussed.

LikeLike

John,

Thanks so much for sharing your interview with author Peter Winkler. You know as many times as I’ve put 4 hrs aside to see Giant again I somehow missed Dennis Hopper. How is that even possible? Really interesting story on how “Easy Rider” came to be.

On Hopper’s art, I recently took the virtual tour of his home after it came up for sale and I think it was even featured on a design show recently. He had quite the eye for art and his paintings on display were quirky but incredibly beautiful. How lucky was he to get a Warhol, an iconic Warhol for a song?

I’ll be adding this book to my vast reading list.

Thanks again for bringing us such interesting posts. You ability to get such sought after interviews is a real treat.

Page

LikeLike

Thanks Page! Looking at GIANT or REBEL WITHOUT A CAUSE now I find it amazing how young and innocent Hopper looked when compared to his later days, say in BLUE VELVET.

The book is a fascinating read. I hope you enjoy it.

LikeLike

John, I read this a day or two ago but didn’t have time to leave a comment then, so I’ve returned to leave one now. A thoroughly enjoyable post. You are really becoming quite the expert at this kind of author interview. Your thoughtfully conceived questions elicit really fascinating details about both the author and the subject of the book. The impression I get is that like a lot of creative people, Hopper was an egotist who could be a very difficult person to get along with, much less work with. I found the part about how Hopper used his photography to prepare himself for movie directing of particular interest. I’m looking forward to the next installment.

LikeLike

Thanks R.D. Hopper was definitely an egotist. Like author Peter Winkler says in the interview, and in his book, Hopper felt he was a genius, unappreciated in Hollywood. He found more acceptance in the art world. Part two will be up tomorrow morning! Thanks again!

LikeLike

[…] This is part two of my conversation with author Peter L. Winkler whose new book, “Dennis Hopper: The Wild Ride of a Hollywood Rebel” is now available. The book brings you inside the world of one of cinema’s most beguiling characters. For part one of this interview click here. […]

LikeLike

Yes Hopper had an enormous ego, and this was basically politely posed by Mr. Winkler in this first part of the interview. yes, the problems between Hopper and Fonda, must surely be attributed to Hopper. Also, I can’t blame Winkler for spending a good part of his work on the making of “Easy Rider,” which of course is teh film that catapulted Hopper to fame. Great interview questions and responses John!

LikeLike

Thanks Sam. The EASY RIDER portion of the book is fascinating, though I have to say so is the rest of the book, however from a historical perspective, that particular film deserves the attention Peter gives to it. thanks again!!!

LikeLike

[…] beautiful. Hopper, who was in a bad way with drugs and alcohol during this period of his life (read my interview with Hopper biographer Peter L. Winkler), still manages to be inspired enough to give a fine performance along with his magnificent co-star, […]

LikeLike

[…] straightforward and took no crap from anyone (see my interview with Dennis Hopper biographer Peter L. Winkler who talks about Hathaway’s battle with young know it all Hopper and how he single handedly […]

LikeLike